The story of Chinese feminism is one of remarkable resilience and transformation. From ancient Confucian constraints to the digital activism of today, Chinese women have navigated complex cultural and political landscapes in their pursuit of equality. Through a psychoanalytic lens, we can uncover the deeper psychological dimensions of this journey, revealing how Chinese feminism represents not merely a political movement but a profound evolution of female consciousness.

The Weight of Tradition: Female Psyche in Pre-Modern China

In traditional Chinese society, women's identities were circumscribed by Confucian doctrines that positioned them as subordinate to men. The "Three Obediences and Four Virtues" formed the psychological architecture of female identity.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, women's id (primitive desires) was severely repressed, their ego (mediating mechanism) was weakened, while their superego (internalized social norms) became extraordinarily powerful. Women internalized patriarchal structures as self-limiting psychological mechanisms, establishing what Lacan would call a subordinate position in the "Symbolic Order."

Women were defined as the "Other," with their self-perception largely dependent on their relationships to men. This dependency resulted in weakened subjectivity and an unconscious reliance on authority, forming cultural archetypes in the female collective unconscious that determined how women perceived themselves and their place in the world.

Early Awakening: Psychological Rupture (1897-1949)

Chinese feminism emerged during the late Qing Dynasty's social reform movements. In 1897, the Chinese Women's Study Society was established, publishing "Women's Journal," which criticized foot-binding and advocated for women's education. In 1903, Jin Tianhe's "Women's Bell" proclaimed "Long Live Women's Rights" and called for women's political participation.

From a psychoanalytic viewpoint, this period demonstrates what Lacan called the "Mirror Stage": Western modernity served as a "mirror" allowing Chinese women to see possibilities beyond traditional definitions of selfhood, triggering an awakening of self-consciousness.

Women's psychological structures exhibited significant tension. The traditionally ingrained superego continued to regulate their behavior, while the awakening ego aligned with repressed desires, seeking autonomy. This internal contradiction produced what Erich Fromm called the "Escape from Freedom" double-bind: women simultaneously yearned for liberation while fearing the loss of security that tradition provided.

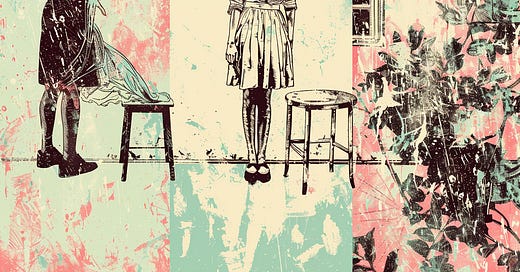

Early feminists manifested extreme forms of this conflict. Through psychological "sublimation," they transformed internal conflicts into revolutionary energy. Their acts of cutting hair, wearing men's clothing, or using masculine pen names represented attempts to create new female subjectivity, often accompanied by intense internal splitting and identity anxiety.

Institutional Empowerment: The Divided Self (1949-1978)

After the founding of the People's Republic, institutional empowerment became the main theme of women's liberation. The 1950 Marriage Law abolished feudal marriage practices, and the 1954 Constitution established gender equality principles, granting women legal subjectivity.

During the Great Leap Forward, the "Iron Girls" phenomenon reconstructed female value through labor competitions. Mao's famous slogan that "women hold up half the sky" incorporated women into the national production system.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, women's self-identity underwent profound reconstruction. The socialist state established a new female role model—simultaneously producer and mother—creating a particular kind of psychological splitting.

This transition created a psychological "double bind": women were expected to participate in production like men while maintaining traditional maternal roles, now reframed as "revolutionary motherhood." This contradictory demand subjected women to endless "overcompensation"—they had to work harder than men to prove they could both "hold up half the sky" and maintain a household.

This psychological structure reflected how collective ideology repressed and reshaped individual desire. Women's personal desires were "sublimated" into dedication to the state, creating a unique "political sublimation" mechanism that granted women new social power while maintaining certain gender constraints.

Reform Era: Multiplicity of Self (1978-1995)

The Reform and Opening era brought economic liberalization and ideological pluralism. Western feminist thought provided Chinese women with new intellectual resources and theoretical frameworks.

However, market economics also brought new challenges. Gender discrimination in employment emerged, with women facing the "glass ceiling." Traditional gender concepts were repackaged in commercial culture, commodifying women's bodies.

From a psychoanalytic standpoint, women's self-identity became increasingly diverse and complex. Julia Kristeva's "subject-in-process" theory aptly explains this phenomenon: female identity was no longer fixed but in continual reconstruction, flowing between traditional and modern, collective and individual, family and career identities.

Economic development offered women more choices but also brought what Sartre called the "vertigo of freedom" and existential anxiety. Women simultaneously experienced two crucial psychological shifts—awakening as desiring subjects and commodification as desired objects, creating fundamental tension and paradox.

In market economics, the female body acquired new symbolic value as an object of consumption. Meanwhile, economic independence awakened women as autonomous desiring subjects. This dual identity created psychological "subjectivity rupture": when women attempted to become desiring subjects, they couldn't escape objectification; when they utilized their "object value" to gain social resources, they might reinforce their object status.

Global Dialogue: Reconstructing Identity (1995-2010)

The 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing marked a milestone in Chinese feminist development, introducing "gender mainstreaming" and promoting anti-domestic violence legislation. This event also signaled dialogue between Chinese feminism and international feminist movements.

With internet proliferation, women's issues gained broader discussion spaces. The internet provided platforms for expression, allowing women to share experiences and form collective consciousness.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, women began redefining themselves. Through global dialogue, Chinese women encountered diverse feminist theories and practices, acquiring new linguistic symbols and conceptual tools to rename and understand their experiences. The introduction of "gender" as a concept enabled women to connect personal predicaments with social structures, reducing self-blame and enhancing collective consciousness.

The internet provided what Kristeva calls a "semiotic chora"—a pre-linguistic, fluid expressive space allowing women to safely experiment with different identities and express repressed emotions. This "identity experimentation" served a therapeutic function, helping women integrate split aspects of self and form more complete self-awareness.

Digital Feminism: Multiple Consciousnesses (2010-Present)

Since 2010, with social media's rise, feminism has displayed increasingly diverse development. From "leftover women" discourse to the 2018 #MeToo movement to anti-domestic violence legislation, women's issues have gained broader social attention.

However, challenges persist. Traditional family views still constrain modern women through stigmatization and objectification. Contemporary women face double disciplining in body politics: tradition demands chastity, while modern consumerism commodifies their bodies.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, contemporary women face multiple psychological dilemmas:

Identity Fragmentation: Lacan's "split subject" theory explains how women must coordinate contradictory subject positions. This splitting produces what Lacan called the "irruption of the Real": when contradictions between different self-identities cannot be reconciled, deep anxiety results.

Generational Replication: Freud's "repetition compulsion" reveals how mothers' unconscious expectations often repeat in daughters. Many women haven't psychologically "been born" as independent individuals but exist as containers for their mothers' unfulfilled wishes.

Language Predicament: Bourdieu's "symbolic violence" reveals how women must use patriarchal language to express themselves yet cannot accurately express female experiences in this language, creating what Kristeva called "female aphasia."

Body Politics: Women face contradictory "purity" versus "sexiness" standards, reflecting Freud's "castration complex" dilemma: either identify with traditional values and repress sexuality, or accept commodification and lose subjectivity.

Technology has created new possibilities but also new complexities. Social media provides platforms for women to break silence and challenge "second sex" identity while simultaneously creating new "gaze structures," with women's self-expression influenced by "imagined audiences."

Nevertheless, younger-generation women are experiencing an important psychological transition—shifting from what Fromm called "escape from freedom" to "quest for freedom," indicating new directions for Chinese feminism as they integrate multiple identities into more coherent self-structures that acknowledge both shared gender experiences and individual differences.

You’re right, and indeed, the state has made significant policy shifts to encourage higher birth rates. This pressure is not new—it’s part of a longstanding cultural force, as you mentioned, which has been “revived” rather than introduced for the first time. Fortunately, the voices of feminism in China have grown stronger, and women now have more resources to reflect on and resist this pressure. While this pressure undoubtedly still exists, awareness of it is much higher, and there is a growing movement to question and challenge it.

Interesting!! How do you fit in the new (revived?) pressure on women in China now to have more children?